LLM inference is nearly deterministic. We use this to audit providers

Adam Karvonen, Daniel Reuter, Roy Rinberg, Luke Marks, Adrià Garriga-Alonso, Keri Warr · arXiv (paper link) · Github

One Minute Summary

Today there’s no reliable way to verify that an inference provider is actually running the model they claim, as they might be using quantized weights, have implementation bugs, or cut other corners. However, it turns out that LLM inference is nearly deterministic when you fix the sampling seed. In our experiments, when you fix the random sampling seed and regenerate an LLM’s output, over 98% of tokens match exactly. Token-DiFR exploits this to verify inference: just measure how much the inference provider’s tokens diverge from a reference implementation given a shared sampling seed.

This means you can detect any problem with the inference process, from sampling bugs to watermarking to quantization. For example, we can detect KV cache quantization with ~10,000 tokens and 4-bit model quantization with ~1,000 tokens. The method works with unmodified vLLM, has zero provider overhead, and any generated output token can be audited post-hoc. Even without sampling seed synchronization, you can audit any inference provider today using temperature-zero sampling.

Introduction

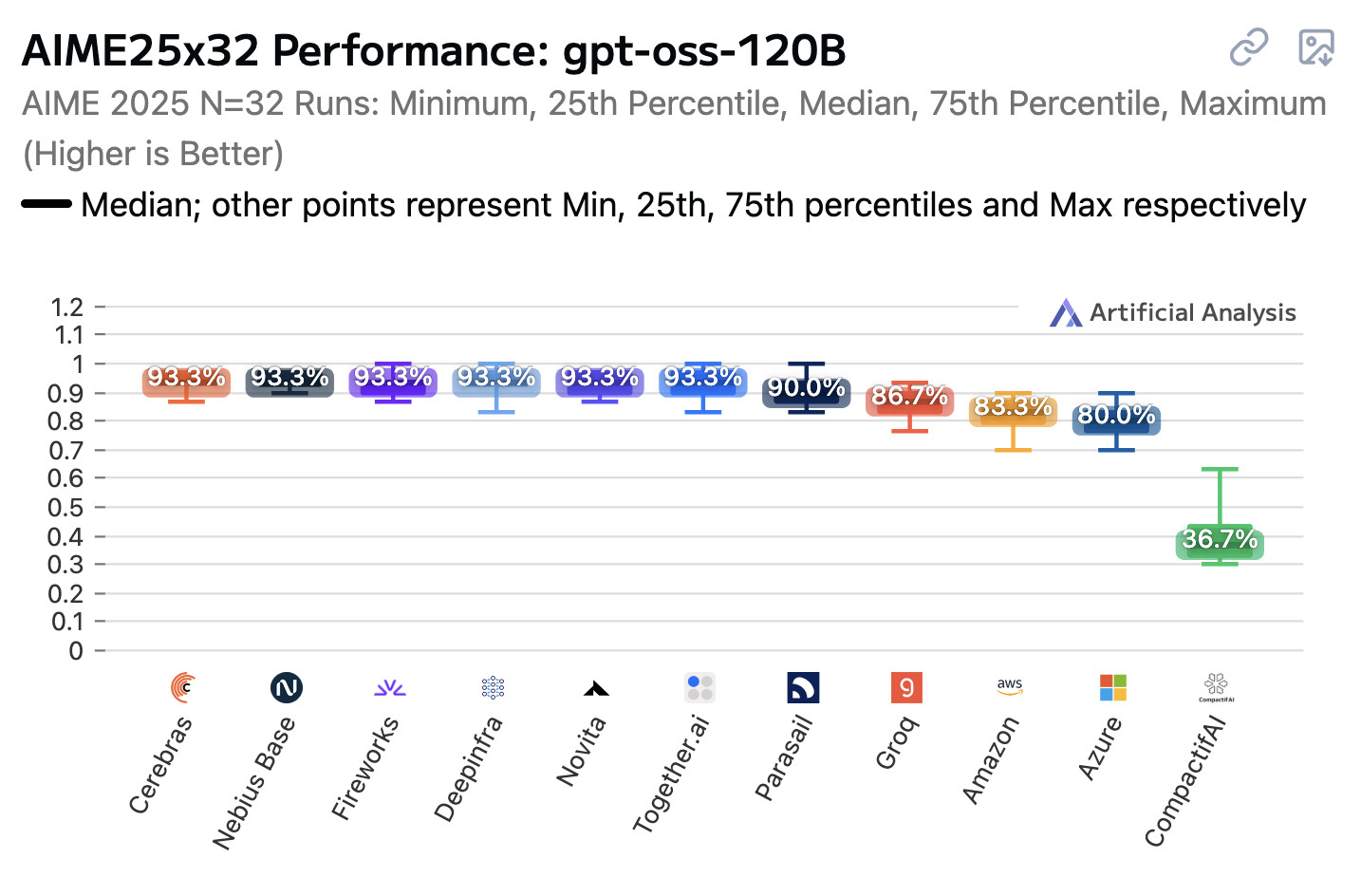

Ensuring the quality of LLM inference is a very hard problem. Anthropic recently disclosed that they had suffered from major inference bugs for weeks, causing Claude to randomly output Chinese characters and produce obvious syntax bugs in code. There are frequent allegations of inference problems with inference providers, and open weight models often have different benchmark scores depending on which inference provider you choose. Sometimes this is due to inference or tokenization bugs, and (allegedly) sometimes this is because inference providers quantize the model to reduce inference costs.

Today, inference quality is the Wild West. You hit an API endpoint and hope for the best. Benchmark scores provide some signal, but they’re noisy, expensive to run, and rare bugs (like randomly sampling Chinese characters) might not show up at all. What if there was a better way?

In this post, we focus on the problem of “inference verification” - concretely, given a claimed model (e.g. GPT-OSS-120B), input prompt, and an output message, can you verify that the message came from the model.

The Problem: Valid Nondeterminism

The obvious solution is to just rerun the prompt and check if you get the same output. Unfortunately, this doesn’t work, as LLM inference is non-deterministic; even with a fixed seed or sampling temperature 0.

Token generation happens in two steps:

- Forward pass: First the model generates a probability distribution over the vocabulary of tokens, by running billions of floating-point operations.

- Sampling: A token is randomly drawn from that distribution. This step is deterministic given a fixed random seed.

Due to floating-point arithmetic, the forward pass step has small numerical noise that can vary across hardware, batch sizes, and software stacks.

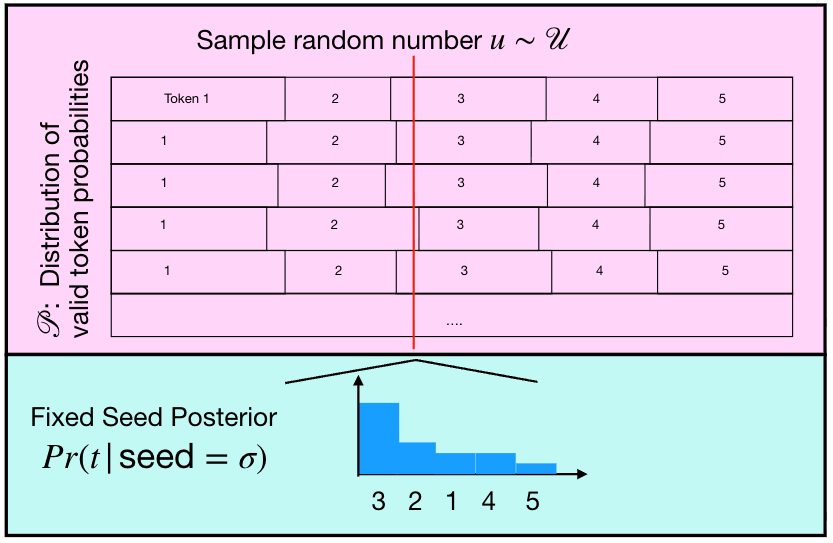

So if you fix the sampling seed, why doesn’t everything just match? Because the floating-point noise in step 1 means slightly different probability distributions, which can occasionally flip which token gets selected, even with identical sampling randomness.

We visualize this through this diagram of the Inverse Probability Transform sampling process (a common method for sampling from a distribution) introduced in our concurrent paper, Verifying LLM inference to Detect Model Weight Exfiltration. In short, consider that there are small variations in the distribution of token probabilities (rows in the pink rectangle), then even if you fix the sampling process (the red line), there is more than 1 “valid” token you may sample.

The Solution: Token-DiFR

However, it turns out that this sampling process is almost deterministic. Empirically, if we regenerate a token with a fixed sampling seed, we generate the exact same token over 98% of the time (in the models and settings we study). When there is disagreement on the next token, there’s usually only 2-3 plausible options. Horace He at Thinking Machines found a similar result: generating 1,000 completions of 1,000 tokens each at temperature zero with Qwen3-235B-A22B-Instruct-2507 produced only 80 unique outputs, with all completions sharing identical first 102 tokens.

Given this fact, there’s a very natural solution: simply measure the divergence between the provider’s token and the verifier’s recomputed token. We call this Token-DiFR (Divergence From Reference). Because inference is nearly deterministic (over 98% of tokens must exactly match), inference providers have minimal room to deviate from their claimed inference process. The tokens themselves become evidence of correct inference, which can be audited at any point.

This means you can:

- Detect a quantized KV cache with ~10,000 output tokens

- Detect 4 bit quantization in ~1,000 output tokens

- Detect an incorrect sampling seed in ~100 output tokens

Thus, verifying LLM inference becomes very simple.

If you’re Anthropic and you’re serving billions of tokens across different hardware (TPU vs GPU vs Trainium) and adding daily inference optimizations, you can simply have a single model instance randomly checking generated outputs against a reference implementation to quickly detect problems. If you’re suspicious of your inference provider, just generate 10,000 tokens and verify these tokens against a reference implementation.

Token-DiFR is Robust to Tampering

Previous approaches verify inference by looking at statistical properties of the output, such as the expected log-rank of tokens within the verifier’s logits. The problem is that these statistics leave many degrees of freedom for a malicious provider. In our paper, we found that measuring mean cross-entropy works well for detecting quantization in the honest case. But it can be trivially fooled, as a provider can just tune their sampling temperature until the mean cross-entropy matches the expected value. Token-DiFR with seed synchronization doesn’t have this problem. Because over 98% of tokens must match exactly, there’s almost no room to manipulate the outputs while still passing verification.

What about implementation differences?

A common objection is that legitimate differences between implementations may cause too many false positives, as inference providers use different hardware, parallelism setups, and inference implementations. However, we found this is not a significant problem in practice.

We tested Token-DiFR across A100 vs H200 GPUs, single GPU vs 4-GPU tensor parallel setups, HuggingFace vs vLLM forward pass implementations, and prefill vs decode phases. We find that the benign numerical noise from these legitimate differences is consistently smaller than the signal from actual problems like KV cache quantization or incorrect sampling configurations1. The level of noise does vary from model to model (Llama 3.1 8B Instruct, Qwen3-30B-A3B, Qwen3-8B), and it does make the detection more challenging, but in all settings we analyze we can still detect FP8 KV Cache quantization, our most subtle quantization setting.

How Does Token-DiFR Work?

In our paper, we primarily focus on a method to verify samples generated through the Gumbel-Max sampling, a common technique for sampling from a distribution, which is an alternative to Inverse Probability Transform. We focus on Gumbel-Max Sampling because it is used by vLLM. Gumbel-Max sampling is simple - generate random Gumbel noise (given a fixed seed), multiply it with the temperature, add it to the logits, and take the argmax logit.

When the provider and verifier use the same sampling seed, they should nearly always pick the same token. When they disagree, there’s a natural score in the case of Gumbel-Max sampling: the logit difference between the verifier’s preferred token and the provider’s claimed token. Larger gaps mean something is different about the model weights, quantization, or implementation. The score can be calculated in these three lines of code:

# logits: shape [vocab_size]

# claimed_token: int, provider's claimed token

# gumbel_noise: shape [vocab_size], deterministic given seed

# temperature: float

logits = logits + (gumbel_noise * temperature)

verifier_token = logits.argmax()

logit_diff = logits[verifier_token] - logits[claimed_token]

In practice, we clip scores to the 99.9th percentile to reduce the influence of outliers.2 Token-DiFR can be applied to any sampling process. We discuss verifying other approaches like speculative decoding in the paper.

How do I use Token-DiFR?

There are two ways to use Token-DiFR.

Shared Sampling Seed and Sampling Process: The ideal is with sampling seed synchronization, where you know the sampling process used by the provider and can send per-request sampling seeds. This means that any output can be audited post-hoc, which provides strong incentives for honest inference. Our implementation works with unmodified vLLM out of the box, and we recommend that inference providers standardize on a sampling algorithm since sampling is not a performance bottleneck for standard autoregressive generation.

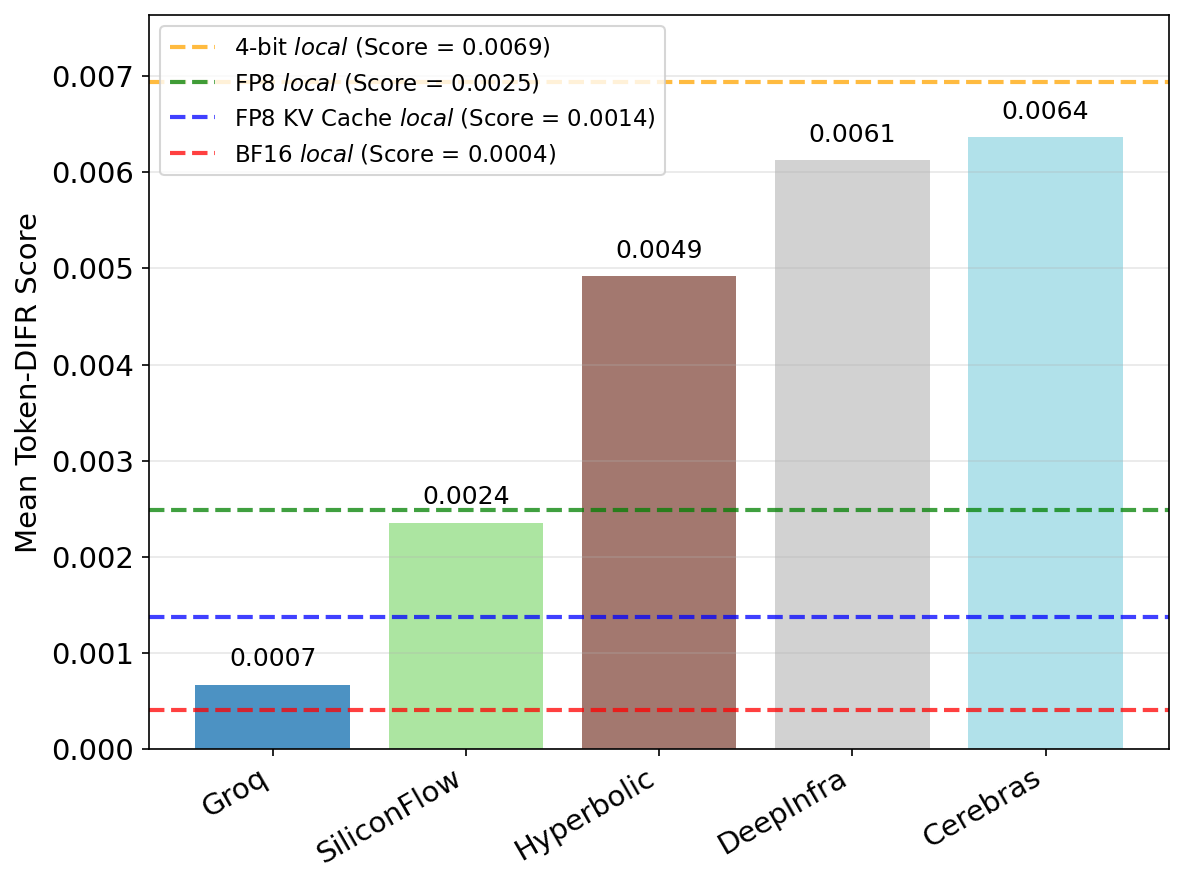

Unknown Sampling Process: If sampling seed synchronization is not available, you can still do spot checks at temperature zero, which bypasses the random sampling process entirely. We did this in our paper for several Llama-3.1-8B providers. Some (like Groq and SiliconFlow) scored very close to their advertised configuration (bfloat16 and fp8 respectively). Others had higher divergence scores, similar to 4-bit quantization.

While low divergence gives high confidence in the provider, high divergence doesn’t necessarily indicate poor quality. When investigating these high scores, we found that at least two providers were using an older Llama-3.1-8B chat template that doesn’t match the latest version on HuggingFace. Currently, most inference providers don’t publish which chat template they use. Publishing this (or just returning the tokenized input) would make auditing more straightforward.

Alternatively, we found that simply comparing the average cross-entropy over a set of prompts works well and can be used in the non-zero temperature setting, although it is vulnerable to tampering as it has many degrees of freedom.

API-Only Verification: Running a local reference implementation for large models (like the 1 trillion parameter Kimi K2) can be impractical. Token-DiFR could be used in an API-only setting if inference providers expose an option to return the top-k logits or log-probs for input tokens. A verifier would generate tokens from the tested provider, then ask the official API to return log-probabilities for that same completion. This would make it very simple to verify providers of large models, like Deepseek V3 or Kimi K2, against the official API. We encourage inference providers to add this option as an API addition that would make ecosystem-wide verification practical.

Activation-DiFR: Verifying the Forward Pass

Tokens are nice because there’s no communication overhead and they work with existing inference APIs. However, they’re low fidelity and discard a lot of the signal available in the model’s activations. Previous work (TOPLOC) proposed compressing activations using their top-K values. This enables accurate detection of, for example, 4-bit quantization within just 2 output tokens. We additionally propose Activation-DiFR, which uses a random down-projection to compress activations. We find this achieves equivalent detection performance while reducing communication overhead by 25-75% (which is typically on the order of 1-4 bytes per token).

There is a caveat: activation fingerprints cannot verify the sampling process. A malicious provider could generate arbitrary tokens and then compute the correct activation fingerprint post-hoc. However, they do verify the forward pass, which represents the vast majority of inference compute and therefore the main economic incentive to cheat. Adding activation fingerprints is a simple step that would make it extremely difficult to tamper with the forward pass without getting caught.

Conclusion

It turns out that verifying LLM inference has a simple and effective solution. We recommend that the community standardize on common sampling implementations, and sampling is simple enough that this should be achievable. Providers who can’t adopt a standard can share their sampling details to enable verification. This will be valuable for both labs monitoring their own infrastructure and customers wanting to trust their API providers.

How To Cite:

@misc{karvonen2025difrinferenceverificationdespite,

title={DiFR: Inference Verification Despite Nondeterminism},

author={Adam Karvonen and Daniel Reuter and Roy Rinberg and Luke Marks and Adrià Garriga-Alonso and Keri Warr},

year={2025},

eprint={2511.20621},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.LG},

url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.20621},

}

And please take a look at our concurrent work applying these methods to detecting LLM steganography and model weight exfiltration -- Verifying LLM Inference to Prevent Model Weight Exfiltration (2025).

-

There is one exception: for Qwen3-30B-A3B, the gap between HuggingFace and vLLM was comparable to FP8 KV-cache quantization. This raises a real question: if two “correct” implementations differ that much, what threshold should you set? In practice, you can choose a reference specification and flag anything that deviates beyond it. The method still works, you’re just deciding what counts as acceptable. ↩

-

When top-p or top-k filtering is used, a claimed token might be outside the verifier’s filtered set, resulting in an infinite logit difference. Clipping handles these cases. ↩